Elle Woods: On the Other Side of Oppression

As a pro-feminist queer who whole-heartedly endorses radical feminism, I took myself to task for admiring the ‘post-feminist’ film Legally Blonde when I saw it the other day. Is Elle Woods, a bubbly ultra-pink sorority girl who survives the rigors of Harvard Law while being true to herself, an icon of liberation? Or is she just a pop-culture fantasy of a woman who ‘has it all’ – unrealistic, not to mention, anti-feminist, in how she represents an ideal of empowerment that ultimately only caters to male desire?

Both, I would argue. But let’s first bring those readers up to speed who don’t know the radical from the postmodern in their feminism: while the former position holds that femininity and masculinity are effects of structural oppression and privilege respectively, the latter, valorizing agency over structure, recognizes the plurality of ways in which we can be feminine or masculine, none belonging exclusively on one side of any dichotomy that we can think of. While radfems think of femininity as a handicap to self-actualization, post-feminists do not want to fix the meaning of femininity, positing it instead as an unstable, shifting construct.

Of course it’s difficult to endorse Elle Woods as some ground-breaking icon of anti-establishmentarian feminist ideals given that alpha-femmes like her have always been the favorites of the American entertainment industry. Only now, the trope of feminine-charms comes combined with the trope of empowerment, so much the worse for how that is an even more unattainable ideal for women than traditional femininity. So, nothing liberating about that. But central to the plot is Elle’s struggle as a lawyer who won’t divest herself of her identity, even though she is competing at a game whose rules have been defined by men. She is no Lady Macbeth who needs spirits to ‘unsex’ her and ‘make thick [her] blood’. The male Professor Callahan who hires her for an internship on an actual courtroom case will not only have to accept her pink, scented resume, but also deal with her rejection of his ‘reason’ which required her to reveal the defendant’s alibi against their wishes. Values of sympathy and sisterhood trumped the courtroom reason, and she won the case without having to resort to the alibi which would have destroyed the defendant’s professional life.

And this, dear cynic, is where I see the potential of liberation in this narrative: the liberation of femininity from associations of dependence and weakness.

The bit of theory I shared above can make sense now. While historically, femininity might have been a tool of oppression in patriarchal culture, it is possible to envision a world beyond oppression, and by extension, one where femininity is not a handicap. When oppression is out, what’s left behind is people’s sense of selves. And isn’t it progressive to encourage people to build an authentic sense of self on their own terms free from undue social pressures? Wasn’t this the principle at the heart of all twentieth-century social movements? So why not extend it to a feminine sense of self? If you’re effeminate, you’re dismissed as frivolous, and your expressiveness and grace are called displays of ‘weakness’ and ‘excessive refinement’. Now how objective is that judgment? And don’t get me wrong: there is no fighting oppression by dolling oneself up and playing nice all the time if that’s all you do. Women lack the agency to be assertive, and changing that should be a goal for feminism to work for. But can’t one be assertive while wearing a lipstick? Obviously it’s more than just about self-presentation: a feminine sense of self can engender an ethos that affirms community, embraces difference, celebrates personal affection and sensitizes rational judgment through emotion.

Lest I be accused of ‘essentialism’, I want to make it clear that these values are ‘feminine’ only in the sense that they are labeled as signs of ’emasculation’ or ‘effeminacy’ in a culture that ennobles the ethos of control and repression of emotion, and privileges competition over cooperation. It’s also telling how the words ‘effeminate’ and ’emasculate’ are used to denote a lack of virility, or manly vigor, while the word for womanly vigor, ‘muliebrity’ is much too obscure, and there is none to denote it’s lack. Such labeling is also used more for gender-nonconforming men. ‘Effeminate’ and ’emasculated’ are almost never used for those born and raised as women: it is reserved for males who shun ideals of virility. So there is a systematic devaluation of femininity in which not only women, but also ‘the sissies’, ‘the fags’ and the ‘queens’, not to mention transsexuals, become degraded. Noteworthy among the various ways in which this plays out is the medicalization of femininity: because of the stereotype of woman-as-week, doctors are twice as likely to be diagnose women with depression, even when they have similar scores on standardized measures of depression or present with identical symptoms.1 Similarly, the referral rates of ‘Gender Identity Disorder’ (now called ‘Gender Incongruence’) have a sex-ratio of 6.6:1 of boys to girls – in other words, if there’s a mismatch between your assigned gender role and your sense of self, you’re more easily pathologized if you identify as feminine.2

For this queer guy, ‘masculine privilege’, in the final analysis, is just a prerogative to be selfish and sloppy. Radical feminism might be able to win that prerogative for women, but those of us who reject virility, irrespective of our assigned genders, let us aim higher: for a different world in which, no longer imbued with a sense of shame and lack, femininity can become an ideal for self-realization, beyond the matrix of oppression and privilege.

______

1. Callahan, E.J. et al. (1997). “Depression in primary care: patient factors that influence recognition.” Family Medicine, 29: 172-176.

2. Kenneth et al. (1997). “Sex Differences in Referral Rates of Children with Gender Identity Disorder.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25/3: 217-227.

Being Belindas

The mirror hangs before me

The mirror hangs before me

My long face stares back at me

a pointed chin

whose rounding I dread

A tiny forehead

gleaned from the thick mass

of black hair surrounding it.

At the black hair

now streaked with red

I oscillate between

fascination and nostalgia

The hair, mostly helter-skelter

sometimes, precise in a bun

A glazed eyeball

with its bit of plastic-glas lens

A newly pierced nose–

a shade too large

showing off that li’l bit of green

My ears trying to seek attention

with their multiple studs and rings

which I regard as pets

And a moody mouth.

but on the whole, a face

I can live with.

My skin the colour

of burnt caramel

a thin, supple body

I am unashamedly

in love with.

Bottles and vials lined

in an array on the slab beside me

the daily ritual

of cleansing, toning, conditioning

the creams and the perfumes

the chief kohl that lines my eyes

the earrings in their silver box

the cupboard with its

greater assortment of clothes

than i could ever wear

the occupational hazards

of being a young girl.

Oh Pope, and other misogynists!

We love being Belindas

and Belindas we shall remain

with our bottles and our vials

our bibles and our billet doux

and we rebel against rapes

of our locks and otherwise.

our bodies and their vagaries

and tricks we play with them

are ours.

And not playthings or objects

for your phallus

or that inglorious phallic symbol

your pen.

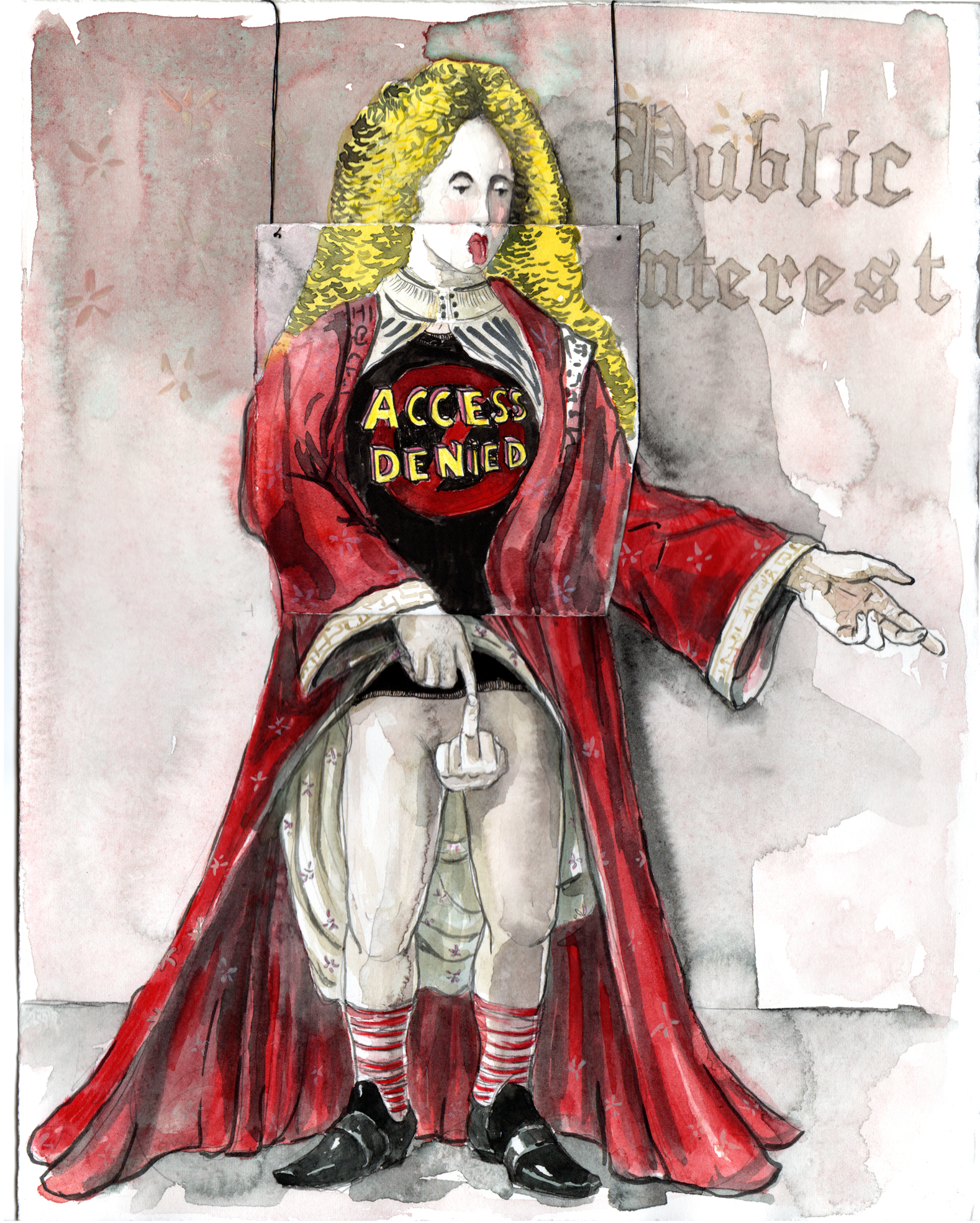

All Oppression

It’s been a while. We at Chay Magazine have been reassessing, rethinking, revamping and also resting and recreating as we figure out where and how to take this publication. Much has happened in the months since you last heard from us. Much of it has been horrible, such as the massacre of Ahmadis in Lahore in their own mosques. So now, as we move forward with a new look and some new opportunities, we also possess a new mission.

When we began two years ago, our mission was to talk about that which we do not talk about; not just say “chay” when we mean “chootia” or “chaalaak” or “charya”; not hide behind culture and civility those things that make us human, that are at the core of our being.

We chose sexuality because sexuality is the hardest spoken of and most difficult of challenges to Pakistani society and norms of acceptable behaviour. But we are finding that there are so many things we do not speak openly about, so many symbolic “chay” words that it isn’t enough to pick a niche and stay in it. Not talking about sex and not talking about religious difference are intertwined because we are equally silent in the face of sexual violence and a massacre. What is it that allows us to be up in arms about drawing images to the Prophet, but leaves us silent when a teenage girl in gang-raped in police custody for over three weeks. These silences must have the same root – they are all linked to possessing “sharm” and keeping your head down and not getting involved with things that don’t concern you. They are related in equal measure to occupying a privilege position in society, whether by virtue of money, or gender, or religion, and the fear of being deprived of privileges. In the words of activist poet Staceyann Chin: “all oppression is connected, you dick.”

So this summer, as we being our third year in publication, we say, “bay se Bol.” All oppression is connected and we must bring it all to light.

If you are looking for a place to voice your views, be they on sexuality in specific or the unspeakable in general, Chay Magazine is your platform. We will still and always centre sexuality and our bodies, but we recognize that aside from desire, love and identity, our bodies also experience war and violence and enlightenment and knowledge and God. We wan to talk about all of it. We believe, above all, in conversation.

Write in to chaymagazine AT gmail DOT com and tell us what you want to talk about.

A Gay of No Importance

It has been an audacious and difficult decision for me to finally come out and accept my gaiety. Coming out has seemed like deliverance from my every sin, for which I will be pardoned and will start living happily hereafter.

But I forgot that life isn’t a fairy tale with a King Midas with a golden touch or a magical kiss which can transform a toad into a handsome prince. I used to think that my perennial tears for being unaccepted and unloved would be gone as my queer folks will take me in with arms wide open. But it turned out to be a different story. I was unaware that my gaiety has to go through a lot of litmus tests before I could be certified as an Authentically Valid Gay. Continue reading “A Gay of No Importance”