…when words found mouths

when tongues wagged their way

into minds,

and each object shrank, suddenly,

to fit its own precise outline.

You could say

that was when the trouble started:

When things stepped into the cage

of a purpose I must have had

somewhere in my mind.

– Imtiaz Dharker, ‘Words find Mouths’

What is in the name: homosexual? If you say it again and again, homosexual, homosexual, homosexual, it begins to sound like a creepy symptom. It is one of the bad habits of words, to give way on the slightest bit of repetition. The word leaks out of itself on being repeated, becomes what it originally (!) was – the deceived one brought into the menacing contract of meaning making. Repetition is a paradox: it both consolidates and shatters. To repeat something is to validate it, confirm its thereness and give it a nod of approval, like in a chant or in sloganeering. At the same time, repetition, for repetition’s sake has a sincere cheek; it kills the word with a master stroke: pulls it out of contingent frameworks and shows the ghastly madness of the name, like in the babbling of a child.

Give a slogan to someone who’s three and you would know. The words straight, lesbian, gay, homosexual, MSM are names with the classic weaknesses of names; words which totter if they are not continuously and shamefacedly propped up by dense political, medico-legal or religious frameworks of conception that are consubstantial with their usage. Every name is a product of a particular framework. The name does not define; it is rather a variable within a hopelessly circular (infinitely repeatable!) process –that first gives the premises of naming and then performs the act of naming based on these premises – and then smugly locates this whole process at the origin of things, before everything else, ala ‘I am gay’, ‘Are you a lesbian?’, ‘We are queer, we’re here, get used to it’, exercises in definition-making, processes of self-identification, loveable repetitions but not simply so!<\p>

I am not sentimental about LGBT activism (with about twenty years of a movement behind us in India, no one better be!) but I would be a part of all of it all the same, with an unforgiving self-irony and a constant clapping on one’s own head. Queer activism, here and now in Delhi, as I have lived through for the past three years, is composed of varied definitional excursions that are precisely that, definitional excursions, baggy monsters, simplifying technologies that take enormous and complicated raw material, lets say of the morass of human sexuality (itself a finished product of another technology), and try to produce, indeed with success, finished products, peculiarly sexualised individuals, gay or straight. These are historical occurrences; contingent responses for a world that can only be handled with strategic generalisations, with the steady repertoire of names, with banners asking for gay rights, hijra rights, lesbian rights, or with pleas composed of canny statistics. Queer activism in Delhi then, composed of a heterogeneous lot of organisations, collectives and individuals, responds practically(!) to this situation of frameworks. For the current case that the Naz Foundation and Voices Against 377, a collective of several queer, child-, women’s and human rights groups, are fighting in the Delhi High Court against the anti-sodomy law in the India, section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, we (the activists? I won’t dare choose to speak for everyone, though!) would present ourselves as minority legal subjects within the immediately available framework of the Indian legal system. Using the weapons at hand, we would shape ourselves strategically and then indulge in another process of self definition: legal State citizens, Indians, sexual minorities et al. That some of us provisionally or really buy into such logics of articulate, if not artificial, self definitions and make them the markers of understanding ourselves for ourselves (in our personal diaries!), can not and should not be denied. Politics is a name for strategies; the desire for and the social process of change have to make use of available names, categories and obstructions and then plunge into a continuous process of remoulding these. We can not start (or end) with something that is already mutatis mutandis. Queer activism, as I have seen in process in Delhi, is the utopian process that deliberately excludes the possibility of a Utopia. A utopic process that finally understands the concept of Utopia (for it is only the concept we can possibly discuss; Greek ‘ou’ is ‘not’, topos is ‘place’, ‘utopia’ is a ‘noplace’, it does not exist!). The Utopia is the defeat of all that is utopian and not what we could and have always easily and non-rigorously believed in, that – Utopia is a the realisation of the utopic. The Utopia is implicit within the utopic; it does not follow it like a flower does a bud or like a child does a foetus.

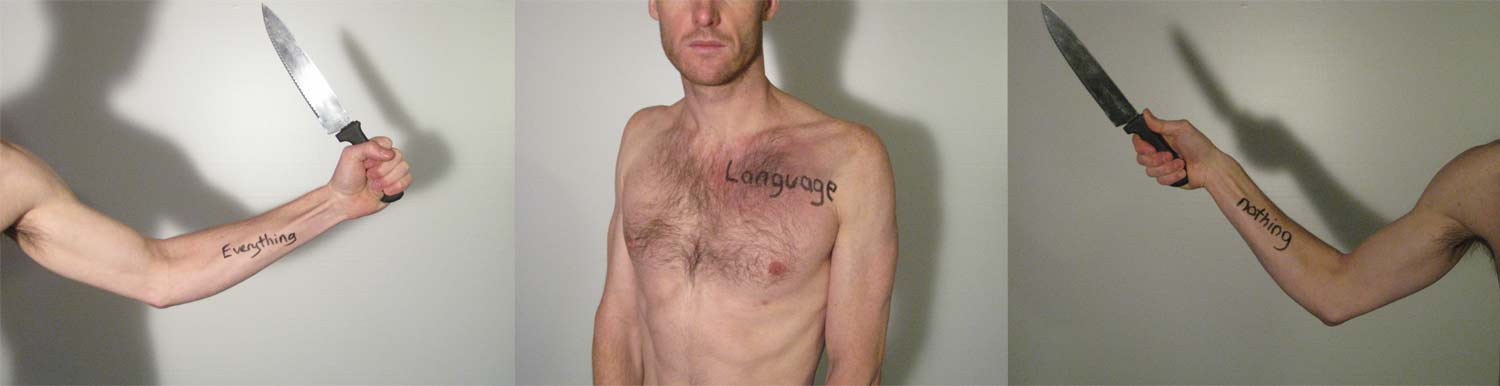

This is not to think about the process of naming as simply undesirable or desirable within activist agendas, to get caught in the enquiry of whether it is right or wrong. To say that the concept of the name works contingently i.e. historically, that we circularly imagine them into being within certain points of history, is not to say that they are unreal or fantastical with no palpable effects. The imagined, with all its imports, can hardly be dispelled or easily demarcated from the real. There is no escaping the realities of the name (as if that was desired or possible; names are the basis of how we interact, it is how we generalize ourselves, names mark our presence even when we are absent, kill me, I’ll still be known by my name! The name is everything!) but it is possible for all of us to see what conditions make what names possible for which people within certain moments of history. I could call myself gay; have done that in the past, might do that in the future, but what are the stakes involved; here, not the stakes of security, rather the stakes of the very process of finding and legitimating a name for oneself, queer for instance, or even Akhil. When and how does the fact that I love men (and sometimes women), that I want to fuck them or get fucked by them, become a variable for what I – want to – call myself? When does the sex-bit get into the name-bit and how does this process work? When does desire become sexuality or sexual-orientation i.e. if it does exist prior to them? Queer activism considers that it is significant to resurrect the sex-bit within the name-bit. The heterosexual poses as the unmarked sexuality, it is the presupposition, the grounds we took for granted. The heterosexual need not name himself; he is the beginning of things, he is unlimited dark space. The queer then appears as a name that queers; the sex-bit in the name-bit marks the different sexuality, the light from a chink. This marking is a politically indispensable process and politics rushes in my veins (another way to enter oneself, to access and define oneself!), so that I have no way to describe myself without names that do not already try and define something about me; otherwise they would be non-names (ideal, theoretically truly queer, stupid utopias!).

Queer activism is strategically played amidst this game of names. We commemorate the first gay protest in Delhi, the AIDS Behdbhav Virodhi Andolan’s public protest against police harassment of gay men, on the 11th of August, 1992, we co-memorate this event and its participants; collectively memorialize the first gay protest that then (threatens to) become our common undisputed history as stringed together through a certain name (they were queer, we are queer!). Names are these trajectories we carve for ourselves and others that are carved for us within the otherwise perversely multiple ways in which histories of individuals or a people can be drawn. One of the events that my queer collective Nigah (nazariya? nazar? a way of looking? a perspective? a name?) organised to mark this now historic date of August 11th was when we met at a particular venue at Cannought Place, made presentations about queer urban histories, talked about them, talked about personal experiences and all our first protests, loves, kisses, and then wore T-shirts that we had painted a day ago and walked around the inner circle of Cannought Place wearing those T-shirts with red roses in our hands (the first(?) public LGBT gatherings in Delhi used to happen on the terrace of the India Coffee House in CP; they used to keep a red-rose on the table as a clue, a locally acknowledged symbol; we chose to extend this curve of history, keep on a tradition, use their strategy of self-identification, use their name) and finally got together in Central Park and ended the evening with more songs and chats. The T-shirts we wore (see Figure. 1) on that day with slogans such as 377 Stinks, We’re Queer, We’re here, Get Used to it!, Aadmi hoon Aadmi Se Pyaar Karta Hoon, Queer and Lovin It!, Aawaz Do Hum Anek Hainet. al. function like names; they form a visual vocabulary for self-identification within a dense public space like CP in Delhi. They want to disrupt the unmarked heterosexual space, dirty it and produce effects of other and strategic namings and spellings (new spells that we cast?). These names, as I have pig-headedly (?) tried to drive home the point, are not at the beginning or the end of things; they are caught in the mire, just like the people they seek to stain.