At first peek, a queer streak pervades the air of Taxal Street, the innocuous commercial area near Rang Mahal, Lahore. The woman who ventures outdoors is yet to be discovered here. Poorly dressed men inhabit it; meeting, chatting, eating, travelling and doing all else amongst each other.

Many shops operate here. Most of their owners are housed in the vicinity. Some – out of necessity not choice – have had to hoist canopies out the back doors of their houses to earn their incomes. Numerous shops have had their shutters drawn for months. In fact, perhaps the most persistently hardworking of all professionals here are the beggars, people whose creativity has made a profession even out of poverty.

The beggars and shop owners are often at odds with one another, each feeling deprived of good business by the other. But even the people of Taxal street have places where they are at peace with their competitors, where elements normally in conflict act in harmony, where even sworn enemies pretend to be brothers, where hypocrisy is made a virtue. These, of course, are the mosques.

There are many of them in the vicinity, but men flock around one more than any other. A plethora of shops surrounds it. Only one of these is open. It turns out that the owners of this shop are also the caretakers of the mosque. “We are thankful to the Almighty for choosing our shop out of all of those around for His blessings,” says one of the caretakers reverently. When asked to hypothesize why all the other shops are closed, he has a ready answer: “This is a sign of divine providence. These other shop owners, they were cold, calculating businessmen and contributed nothing to the maintenance of the mosque. We aren’t like them. That is why we have the patronage of Allah.”

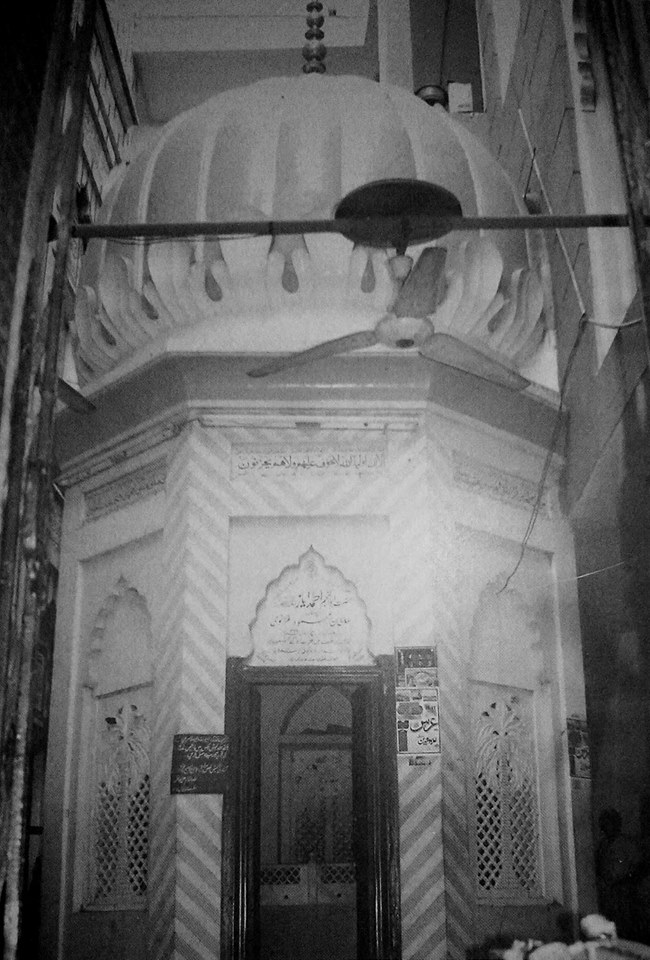

The mosque does not cover a lot of ground, but what it lacks in breadth it makes up for in height, with its only tower standing proudly erect, surging higher into the sky than any of the surrounding structures.

At the very centre of the mosque is a shrine, a hexagonal room raised on a platform containing a grave marked with the name “Ahmad Ayaz”. Though the walls are cracked, the shrine is clean and well-lit. The tombstone is adorned with vibrant orange garlands and multicoloured rose petals glistening vividly are scattered over the rest of the grave. Their scent hangs outside the entrance door, over which is inscribed an extract from Iqbal’s poetry:

ایک ہی صف میں کھڑے ہیں محمود و ایاز

نہ کوئی بندہ رہا نہ کوئی بندہ نواز

Ek hi saf mein kharay ho gaye Mahmud-o-Ayaz

Na koi bandha raha, na koi banda nawaz

Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi, genocidal invader, conqueror, looter, pillager, iconoclast, slave-trader and Muslim hero had countless slaves in his service. In 1005 CE, he purchased one hundred and twenty more. Ayaz was one of them. It is said that the Sultan experienced in Ayaz love at first sight (or infatuation), despite the fact Ayaz’s appearance was not particularly pleasing to the eye.

When the Sultan was reproached for being so superficial as to fall in love with someone ugly in appearance, he replied, “My love is for his disposition, not for his stature and good height.”

What part of his disposition revealed itself so tellingly on the Sultan is a matter best left to conjecture. But the fact that Ayaz’s effect on the Sultan was mesmerizing cannot be denied: Ayaz was granted royal patronage at once and given a formal education.

As his protégé ripened, the Sultan heaped him with increasing doses of affection. The increasing affection (as it often does) coincided with a steady rise in rank, which reached its summit when he was made General of the Army. All the while Ayaz and Mahmud spent more and more time in each other’s company. In his old age it is said that the Sultan would sometimes even neglect his duties to the state to be with Ayaz.

Ayaz holds the distinction of being appointed the first Muslim governor of Lahore after the Ghaznavid conquest in 1021 CE. He held the office for twenty-two years. In recognition of this, he was given the title “Malik”. The slave had turned ruler.

As governor, Ayaz had only one real responsibility: raising Lahore from the ashes and repopulating its ruins after the great Sultan had torched and depopulated it.

An instance of Ayaz’s devotion to the Sultan is found when one evening the two were dining together. The Sultan peeled and offered a cucumber to Ayaz, who gulped it down with visible relish. A little later he tasted the cucumber himself. But it was so unsavoury that he could not swallow its contents and had to spit them out. Enraged, he accused Ayaz of tricking him into eating the unpalatable salad by pretending to find it delicious.

Ayaz answered, ‘No, dear Sultan. It really was delicious to me. You’ve given me so many wonderful things that whatever comes from you is sweet to me.’

But Ayaz was not a mere puppet, meekly satiating the overgrown ego of a tyrant. He could pull as many strings to control the Sultan as the Sultan could to control him, and he was distinctly aware of his influence, as can easily be surmised from his famous response when the Sultan asked him if he knew a king greater and more powerful than he. Ayaz answered, “Yes. I am a king greater even than you.” When the king asked Ayaz to substantiate his claim, he replied, “Because even though you are king, its your heart that rules you, and this slave is king of your heart.”

It is a curious thing that of the plethora of the Sultan’s achievements, the great poets of the eastern tradition, such as Sheikh Saadi and Allama Iqbal, should find time only for his love for a slave boy. They see in this love the Sultan’s greatest conquest, the conquest of prejudice.

Yet the only knowledge the caretakers of the shrine have regarding the object around which their lives centre is the story inscribed on the walls of the mosque. The rest they leave to their imaginations.